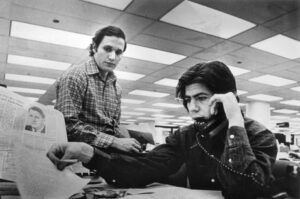

The scoop of the century, heralded in media folklore as investigative journalism at its greatest, was landed by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in the early 1970s. They were only in their 20s. Their story, built around the political intrigue, burglaries and bugging of ‘The Watergate Scandal’, led to 40 convictions and triggered President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974.

The reporters owed a lot of the success to their source, known only as ‘Deep Throat’. Woodward and Bernstein spoke with ‘Deep Throat’ 18 times between June 1972 and November 1973. Everything was ‘on background’ and the points of contact included seven phone calls and six rendezvous meetings in a dimly lit underground parking garage in Virginia.

They maintained a monastic silence on the identity of ‘Deep Throat’ for 33 years until, at the age of 91, the source himself told the world. ‘Deep Throat’ was Mark Felt of the FBI. During Watergate, Felt held the post of Associate Director, the Bureau’s second-in-command. If the trust between the source and reporters had not been established, it is highly unlikely their story would have had the same impact. This is the perfect example of what can happen when journalists keep their word. It is all the more impressive given the intensely gossipy circles that feed through Washington. The discretion influenced the rest of their careers. Future sources always knew their words would be kept in the strictest confidence.

‘Unbreakable Contract’

“This really is an unbreakable contract unless somebody is dishonest with you,” Woodward said in a speech to Harvard University in 2005.

Journalists will do almost anything in the search of a good story and that includes agreeing on parameters. Central to this success is often the protocol of the professional journalist. It is your word against theirs. Trust is everything. Attaining that trust requires an investment of time, diligence and a desire to cultivate a strong network of media contacts.

Rules of the Jungle

When engaging with the media, there are a handful of crucial phrases you need to action, each with a different connotation: ‘On the Record’, ‘Not for Attribution’, ‘Off the Record’, ‘On Background’ and, for investigative journalism, ‘Deep Background’.

ON THE RECORD

In this instance, every detail of the conversation can be quoted and attributed by the source’s name and job title. Anything less must be agreed.

NOT FOR ATTRIBUTION

The content may be used but the source cannot be quoted by name. The reporter can only use on the condition of preserving the source’s anonymity. For example, if the story is about a local mine, the quote may be sourced, “..according to one of the miners.”

OFF THE RECORD

The source’s comments or identity cannot, in any way, be used for publication. This is used best in a one-on-one situation. Question: if you cannot quote then why bother? For the source, it’s an opportunity to shape future coverage. For the journalist, it’s a chance to connect with an influencer, be privy to inside knowledge, and add credibility when they verify the story to the editor.

ON BACKGROUND

Similar to ‘not for attribution’, the content can be used but the source’s identity cannot be revealed. The one difference is that the source may also prefer the comments to instead be paraphrased. Sources use this as protection to share important documents while maintaining their anonymity. For the journalist, it helps to support the veracity of the story, for example, “.. said a company official with access to the information.” Clarify with the reporter how you will be described in the piece.

DEEP BACKGROUND

This information can be used but WITHOUT attribution. The source does not want to be revealed in any way, to anyone, ever, and including on condition of anonymity. This is primarily used by investigative journalists. Woodward and Bernstein used the term when updating Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee. Excellent editor that he was, Bradlee respected the need for confidentiality and never questioned it. As evidenced by Watergate, this information can be used by the reporter to enhance their view of the subject matter, or to act as a guide to other leads and sources. Amateur Night. Be Warned.

With journalists that you either don’t know or make you feel uncomfortable, tread carefully. Your comments can be misquoted, taken out of context or, in the worst case, sensationalised. The damage can often be irreparable. Use your judgment, a lot of caution and ALWAYS record the interview (every smartphone has a voice recorder app). If in doubt, ask the reporter to read back your quote. This is important when speaking with a non-native speaker as he or she can easily misunderstand or misinterpret. Take no chances.

Know the playing field by, first, clarifying that you understand – and agree – the parameters. If your news is politically, financially or personally sensitive, it is imperative you feel safe and secure. Don’t be afraid to step back, mid interview, and ask to go ‘off the record’ or ‘on background’. This is a fair request and should be honoured. Switch off the recorder.

Quality over Quantity

For the naysayers who say journalism is finished. I wholeheartedly disagree. Yes, newspapers and TV are scaling back, and yes, the internet has cannibalised the more traditional platforms, yet digital media grows stronger by the day. With the torrent of information streaming across the web, there is a greater need to disseminate class from trash, fine dining from the junk food. The appetite for quality journalism is as strong as it was during Watergate. In fact, it is stronger. By that, I mean reporting, which is credible, well-written, accurate, properly sourced and tells a compelling story. Formidable vs fake news.